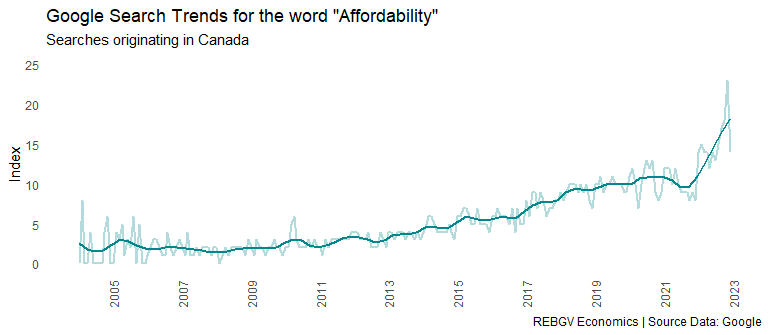

“Affordability”.

It’s a loaded term that you’re likely to have encountered in your life over the past ten years or so, especially if your daily life has anything to do with housing and/or real estate.

And if you’re a politician or policy maker, you’ve probably been paying close attention.

It seems these days, success in being elected, or getting re-elected, increasingly depends on what a politician or political party *say* they are going to do about affordability – whether that be to buy a home, or to buy groceries.

It also seems that Canada’s history is littered with unkept promises to improve affordability from parties of all political stripes.

Consider this plot of home prices across Canada going back to the early 1980s, with shaded bands indicating the political party in power at the time, as a testament:

It’s hard to look at a plot like that and believe that of all the policies aimed toward making housing more affordable, effectively none have ever truly made housing *cheaper*, as measured by the price level.

But this is perhaps an overly cynical view based on too-narrow a metric of success since it’s true that there have been occasional improvements here and there.

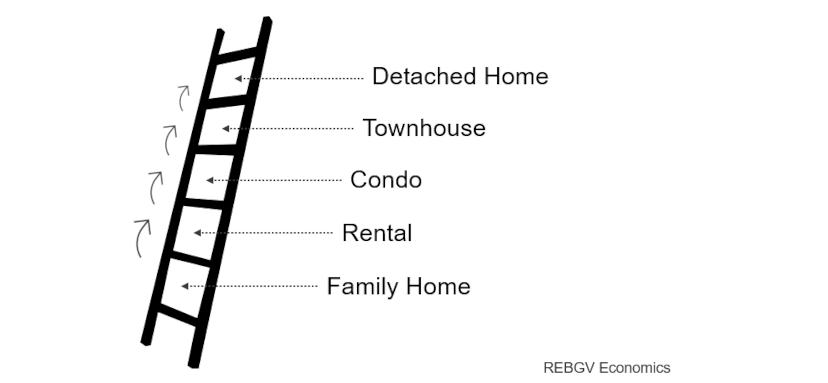

The housing ladder

But it used to be that the pathway to homeownership was clear – a social contract, if you will – where younger generations could expect to achieve homeownership through a stepped pathway colloquially referred to as “the housing ladder”.

Conceptually, it looked something like this:

The idea was that a young household would start out in the family home (assuming they’re lucky enough to have a family home), and they’d eventually move into a rental home outside the family home.

In time, they’d save up enough money for a down payment, and they would step on to the first rung of home *ownership*: a modest “starter home”.

After that, maybe the household size would grow through the addition of children or other dependents, and they’d have built up enough equity through paying down their mortgage to “move up” the housing ladder to a larger home.

And at some point, all households eventually grow so old that all that extra space is no longer necessary and getting up and down the stairs become a nerve-wracking daily experience.

At that point, the need to “downsize” arises, which has an interesting implication for the housing ladder, in that these households need to move *down* the ladder – often by multiple rungs – sometimes even back into rental, seniors housing, or possibly, their children’s home.

The ladder: it’s broken

In the rest of this piece, I’ll argue that today, the housing ladder is structurally broken in many of Canada’s most populous (and prosperous) regions, which has knock-on effects across the country.

And I’m going to lay a good chunk of the blame1 for this structural break on a policy that came into effect only about ten years ago, but which today, has detrimental impacts on housing affordability for all Canadians, up and down the housing ladder.

And in a cruel twist, I’ll show how this policy is actually most punitive to renter households trying to get on the ownership rung of the ladder, which is adding unnecessary pressure on an already-strained rental housing stock.

But I’m also going to suggest a way to fix it, which could be done with the stroke of a pen.

Or maybe a few pens. You know – the fancy type that you dip in ink, with the feather on the end.

And while I can’t say I’m able to offer a solution that would be a true panacea for affordability, I think it *could* help fix things, at least partially.

And – spoiler alert – it’s not without any risks. But it might be that at this current point in time, the risks justify the reward.

D**n payment!

You may wonder what policy I’m talking about?

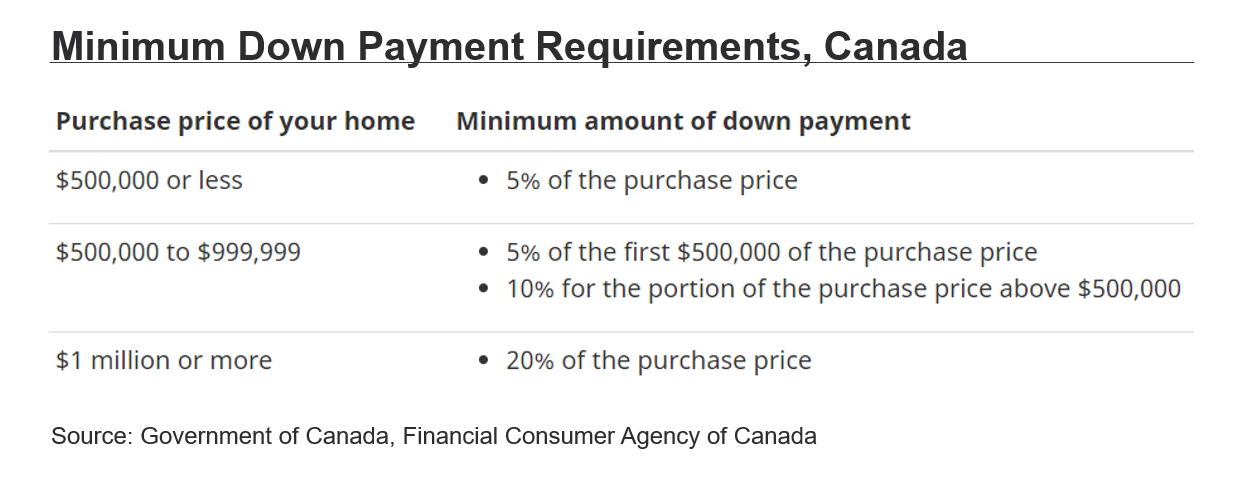

Well, consider this policy setting out the minimum down payment a home buyer must satisfy to qualify for mortgage financing in Canada:

On the surface of it, these requirements seem almost entirely innocuous. Even downright sensible.

And in many ways, they were, back when this set of requirements were amended to be mostly as they stand today by the late Finance Minister Jim Flaherty, in 2012.

But the fact these requirements remain largely unchanged today in 2023, is something I will argue has become a problem for the proper functioning of the housing ladder.

But first, a brief history

Flaherty was facing a particularly difficult economic and political climate at the time he was Finance Minister.

The world was just emerging from the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008/2009, for which causation2 is usually attributed to an enormous housing bubble in the United States which burst around 2007, sending shockwaves throughout the global financial system.

Because of the economic and political climate surrounding the GFC, buzzwords such as “over-leveraged borrowers” and “housing speculators” became mainstream, and no political party of any stripe wanted to be perceived as having enabled this global financial calamity.

And so, Jim, maybe taking cues from the political climate of the time, decided it would be in the interest of all Canadians to strengthen Canada’s financial system by making tweaks to an esoteric piece of legislation known as the Protection of Residential Mortgage or Hypothecary Insurance Act.

Through amendments to the Eligible Mortgage Loan Regulations in 2012, Flaherty removed the ability to obtain government-backed mortgage insurance on home purchases valued at $1 million or greater, among a few other tweaks.

In practice, what this meant was that anyone wishing to purchase a home valued at $1 million or greater would need to put a minimum down payment of at least 20 per cent.

From the perspective of the Federal government: why should Canadian taxpayers backstop loans to the “ultra-wealthy”3 and “speculators”, who might be gambling on properties valued at more than $1 million using government-insured financial leverage?

This all seemed entirely reasonable at the time, and, indeed, it was only a small policy tweak that was lauded and supported by many in the financial and real estate industries when it was introduced.

No big deal. Right?

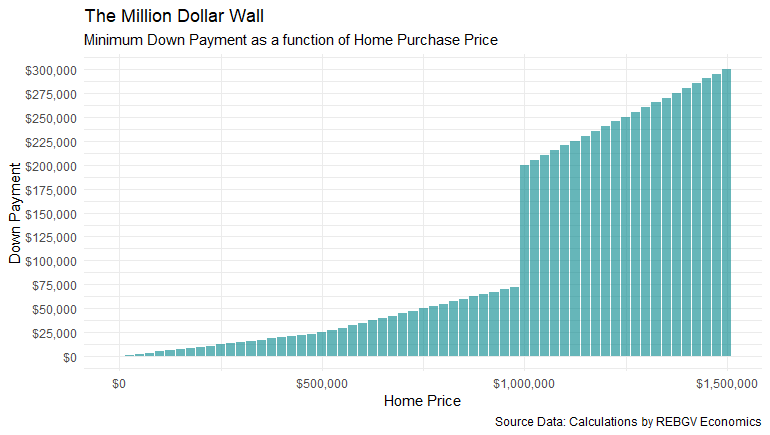

The Million Dollar Wall

And it’s here where the story of our trouble begins.

What exactly is the problem?

Well, it’s easiest to see it if we simply plot out the minimum down payment required for the purchase of a home of incrementally increasing values.

Here’s a plot showing the minimum down payment required for homes up to $1,500,000, in $25,000 increments:

Do you see that HUGE $125,000 jump precisely at the $1 million purchase price?

Yep.

That’s what I’ve been calling4 “The Million Dollar Wall”, and it has become a serious impediment to free movement up and down “the housing ladder” in Canada.

How so?

Then and now

You see, back then (around 2012), only about three per cent of homes in Canada were valued5 over $1 million.

As a result, Jim’s policy tweaks barely had any impact on the market at all, except to reduce (or nearly eliminate) the government’s exposure to mortgages on homes valued at $1 million or over.

And that was exactly the desired outcome.

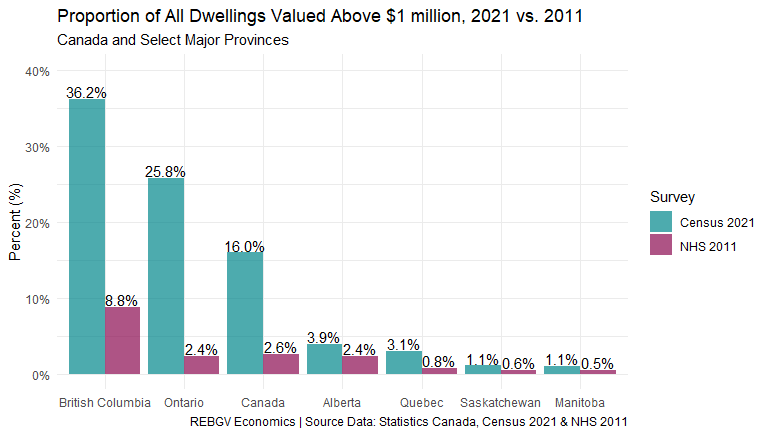

Fast forward to today however, and the fraction of homes in Canada valued over $1 million has risen more than five-fold, growing to approximately 16 per cent of all dwellings, as of the 2021 Census.

But these national-level statistics hide an important fact: two of Canada’s most populous provinces (British Columbia and Ontario) now have *significantly* higher proportions of homes valued over $1 million than the national average, standing at about 36 and 26 per cent of all dwellings in these provinces, respectively.

In fact, it’s precisely *because* these two provinces have such high proportions of homes valued over $1 million that the national average is as high as it is – they’re the ones skewing it upwards!

And I think it would be reasonable to argue that today, *most* homes valued around $1 million in BC or Ontario are hardly luxury properties sought out by speculators.

By and large, many of these homes are now (increasingly) owned and occupied by middle-class folks of fairly “average” means, just about everywhere where you will find them.

And the *reason* these homes are now worth so much isn’t because of speculation or reckless lending on the part of financial institutions – it’s primarily because there aren’t enough homes available for everyone in Canada who wants one.

It’s compelely loonie

To fully appreciate why this has become such a problem today, it’s best to start with a simple example of how moving chains work up and down the housing ladder.

Imagine a fictional world with just four dwellings of varying prices, and four households with differing amounts of savings or equity available for a down payment. There are:

A single in a one-bedroom rental apartment, with $17k in savings;

A young couple who own a one-bedroom condo, with $96k in equity;

A middle-aged couple with one child who own a two-bedroom townhouse, with $130k in equity; and

A couple of empty-nesters in a three-bedroom house, who no longer want to own a home, and are looking to cash out of the market to fund their retirement and world travels. Their equity is equivalent to the entire value of their house ($1.3 million) as they own it outright, having paid off their mortgage.

Now consider what happens if the couple in the townhouse has another child, and they need to move up to the three-bedroom home for the extra space.

If the price of housing was free, the empty nesters would gladly move into the rental apartment, allowing everyone to shift up a rung on the housing ladder, and everyone would be happy.

But the price of housing is *not* free.

And sadly, the couple in the townhouse can’t move up to the detached home, because the home is valued at $1.3 million and they’d need to come up with a $260k dollar down payment, which they don’t have presently – they’re $130k short.

As you can see, the minimum down payment policy regime has effectively created a logjam up and down the housing ladder, all because one single household can’t move up.

As a result, everyone is simply stuck on their rung of the ladder, waiting for the couple in the townhouse to save up the *additional* $130k needed on top of their current equity to move up. But depending on their income and savings rate, this could take years, and it’s even possible they may never be able to save up enough!

No vacancy

And while the plight of our fictional household in the townhouse may seem arbitrarily unjust, the character most harmed by the unnecessary log jam in this fictional story is actually the renter household, who is unable to get a foothold on an *ownership* rung of the ladder.

And as if this wasn’t bad enough, it’s not as though housing options for the renter household are plentiful! It’s well known that vacancy rates in nearly all purpose-built rental housing across Canada are already extremely tight and have been that way for many years.

And it’s clear from the data very few new purpose-built rental units are being added to the stock in BC or Ontario, especially when you look at the net change in the stock of purpose-built rental units since the 1990s6.

It’s true. BC has only added a little over 26,000 units to the purpose-built rental stock7 in the last 30 years, on net.

Fun Fact: the vast majority of the growth in renter households in BC over this period have been accommodated by growth in units in the *secondary* rental market, which are mostly comprised of dwellings rented out long-term, such as basement suites, laneway houses, investor-owned condominiums, and the like.

Oil and water

At this point, you can probably appreciate how this seemingly innocuous policy governing minimum down payments has effectively created a two-tiered system of homeowners (and would-be homeowners) in Canada:

Those *with* $200,000 (or more) in equity for a down payment who can access all rungs of the housing ladder8; and

Those *without* at least $200,000 who are stuck competing for homes on the lower rungs of the housing ladder that don’t require such a significant down payment.

And with all the growth Canada is expecting from immigration over the coming years, competition for homes that *do not* require $200,000 or more in down payment will only heat up as the proportion of all homes valued $1 million and over in Canada continues to grow.

The pressure is building every single day, and it seems as though a lot of this unnecessary pressure can be attributed to having an arbitrary “line in the sand” drawn at properties valued $1 million and over.

What’s so special about $1 million in particular? Why wasn’t the line drawn at $1,234,567.89, or some other arbitrarily chosen number9?

What’s the solution?

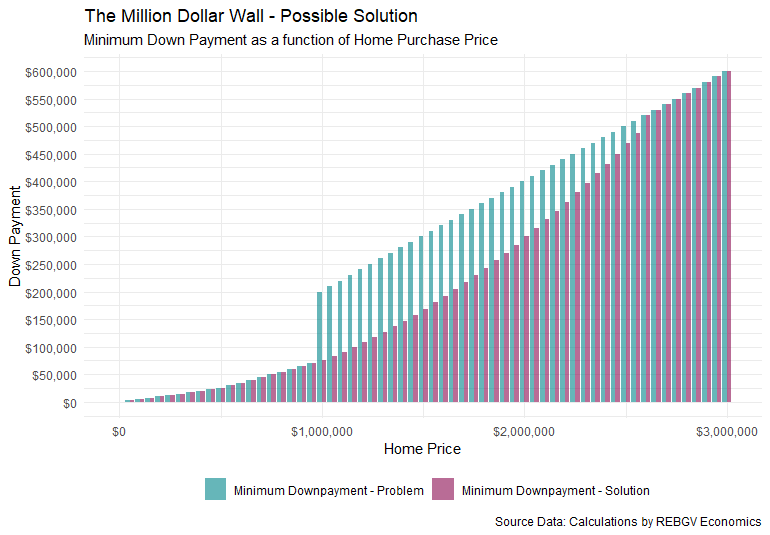

As promised, I do have a simple fix to offer for this problem, which as I said in the beginning, could largely be achieved with the stroke of a pen.

All that needs to happen is the policy governing minimum down payments needs to better align with the realities of the housing market as it stands today, and how it might stand in the future.

How could we do that? There are a lot of possible ways.

But here’s one extremely simple way to do it:

See what I did there?

All I did was change the minimum down payment requirement to a smooth and *gradual* function that increases alongside the purchase price, *without* any giant gaps or leaps, as we have under the current system.

As long as there are no “million-dollar walls” in the minimum down payment required, this simple change has the potential to dramatically improve mobility up and down the housing ladder.

And all it would really take is a serious review of the policy, along with a couple tweaks.

No guts, no glory

In closing, I’m aware the solution I’ve offered is more complicated in practice than in theory.

For one, this solution opens up the possibility of having the federal government backstop *more* of the mortgage insurance market than they already are, depending on how changes to the policy might be made.

One possible implication of this could be (slightly) higher mortgage rates and/or mortgage insurance premiums in the market, to reflect the (potentially) higher degree of risk in the financial system. It’s not immediately clear that this is necessarily “good” or “bad”, per se.

Another possible outcome is that this could shift demand around in the housing system, such that prices for the most expensive homes might appreciate, while those in more modest price ranges might depreciate (slightly) as households stuck in their respective rungs of the housing ladder are (finally) free to move up.

This could be an entirely desirable outcome from a political standpoint – depending on one’s political stripes.

But from a politically neutral perspective, if the overall outcome is better mobility up and down the housing ladder, particularly mobility that frees renter households from being perpetually stuck in near-zero-vacancy rate conditions, is it not worth giving it a go?

Who knows.

Maybe this might actually improve the one metric every politician of every stripe in recent history has failed to materially improve: affordability.

Footnotes

Though not all of it. There are many other important issues plaguing housing affordability as well.↩︎

There are interesting after-the-fact studies which have shown the story may not actually be as simple as blaming over-leveraged housing speculators, but I’ll leave this fascinating sidebar for another time and post.↩︎

As defined as anyone able to purchase a home valued at $1 million or over, back in 2012.↩︎

This graph and its implications have been kicking around my head for years, though it’d be foolish to think I’m the first to ever think about it. But, to the best of my knowledge, I’ve never heard or seen anyone look at this issue quite this way, nor call it “The Million Dollar Wall” (yet). So, maybe I’m the first?↩︎

Calculations are based on 2011 National Households Survey and 2021 Census data, using owner-estimated values.↩︎

Yes. That plot is showing the *net* change in the purpose-built rental stock since 1990, and no, my math is not wrong, and your eyes are not deceiving you. It’s a stark and disappointing fact.↩︎

Some readers may note that CMHC Starts and Completions Survey (SCSS) data show there were over 140,000 “rental” units completed in BC since 1990. But CMHC’s Primary Rental Market Survey (PRMS) captures the *purpose-built* rental “universe” (i.e., the stock) in their annual survey, and these data show that the net change in the actual *stock* of purpose-built rental between 1990 and 2022 was only about 26,000 units. The enormous difference between these two figures is explained by at least two factors: 1. Many newly constructed purpose-built rental units captured in the SCSS were simply replacing existing purpose-built rental units, and 2. CMHC’s SCSS counts units as “rental” which are not considered part of the “purpose-built rental universe” in the PRMS, since the PRMS requires units to be in buildings with three units or more to be counted in that particular survey.↩︎

Assuming they can service the mortgage, etc.↩︎

It’s as though policymakers in 2012 never anticipated that a lot of Canada’s housing stock could ever be valued $1m and over at any point in the relatively near future, which seems quite short-sighted in retrospect.↩︎